The following is commentary on Episode No. 25 ("Giving and Taking") from members of AFAMILYATWAR-LIST. If you wish to add your thoughts to what is being said on this page, become a part of our discussion group by clicking the "Join" button.

Richard Veit

I consider the black and white episodes (nos. 25-32) to be some of the strongest scripts in the entire series. One soon becomes accustomed to the absence of colour, so it really is no problem from a dramatic point of view. Indeed, in a strange sort of way, black and white actually seems to add a certain film noir “edge” to the productions that I find quite appealing.

“Giving and Taking” concerns itself with four troubled relationships: Edwin-Jean / David-Sheila / Michael-Margaret / and Tony-Jenny.

Disparity of class resurfaces when Edwin and Jean are at the old Ashton home in Yorkshire, and she complains that the house smells, the bed is damp, and (referring to Edwin’s side of the family) “They weren’t my people.” He takes exception to these insensitive remarks, and their marriage is damaged at its foundations—their very identities as human beings. At one point, Edwin breaks down in tears and confesses to his wife that he is lost. Characteristically, she offers him no comfort. We sense that the lines of communication between them have become severed. In the context of their marriage, both of them sometimes are guilty of changing the subject or even openly rejecting the other’s attempt at peace overtures, but Jean is particularly guilty of such selfish behaviour. However, we should bear in mind that she is not well. It is two months after Robert’s death at sea, and the physical and mental toll on Jean Ashton is by now clear to see. Whether due to a minor stroke or depression, she suffers from malaise and fits of forgetfulness, and her mind occasionally wanders, causing her to become unaware of where she is. Another manifestation of her illness: after all these years, for no apparent reason, she has resumed smoking cigarettes, an aimless decision that strikes both Freda and Edwin as singularly odd.

Just when David Ashton is making some half-hearted effort to salvage his marriage, in walks Colin Woodcock, and any possibility of reconciliation is dashed. Sheila is innocent of any wrongdoing, but I suppose it is only natural for David to suspect otherwise in the circumstances. Still, it is difficult to grant him much sympathy, in view of his own proclivity for indiscriminate liaisons.

Little does Michael Armstrong realise how hopeless his situation has become. Edwin has learned from Major Dimmock that John Porter is indeed alive, and that all but seals Michael’s fate. Though Edwin may insist to Jean that there is some doubt as to where Margaret’s affections will reside, my feelings are that she is too loyal, too decent, too firmly grounded in morality to abandon her husband for the arms of another man. She will attempt to do so at first, enjoying the bogus freedom of choice, but ultimately there can be no question of establishing a permanent home life with Michael.

I find it quite sad to witness the dissolution of love between Tony Briggs and Jenny Graham. She is such a charming, classy lady that I wish their plans for a life together could have been realised. But it was not meant to be. Tony, that most likeable, eligible, and desirable of bachelors on “A Family at War,” is the one who will remain single at series end. I can see the obvious and insurmountable problems with his cousin Freda and, in “Flesh and Blood,” with Barbara (mother of little Stevie), but the relationship with Jenny was on another level altogether.

Some other comments and questions about “Giving and Taking”…

In this episode, we learn that Sefton’s late wife was named Edith.

There is a funny scene between Sefton and Tony, wherein Tony tries to get his father to admit that he slept with the door open to make certain that he and Jenny did not become too amorous during the night. Ever wily, the elder Briggs attributes his new-found attentiveness to “the burglary.”

How nice it is to have Margaret back with us again after her time away, recuperating in Shropshire. My eyes always seem to gravitate to Lesley Nunnerley whenever she is on screen.

Has anyone else noticed that the young boy who plays John George Porter here, Ben Grieve, is almost always crying? The same holds true in later episodes, too. Was he afraid of the cameras, the sound equipment, and the lights? It does not damage the productions very much, as children of that age do cry, but I wonder what the circumstances were for selecting him for the role. (Is he, perhaps, related to Ken Grieve, a director of Coronation Street?)

The touching scene where Margaret and Freda are in the kitchen, discussing young Robert’s death, is one of the most shattering in the series, powerfully acted by Lesley Nunnerley and Barbara Flynn and beautifully written by John Finch. Another memorable moment comes later in the episode when Freda discovers that she is lying in Robert’s bed. Her look is utterly believable, and I am impressed by actor Colin Campbell’s perfect timing here, as David tells her, “No, that wasn’t my bed. It was Rob…” He stops short of saying his brother’s name, but of course no one can reverse her pangs of sorrow.

What a majestic camera pan director Gerry Mill chooses in that bleak establishing shot of the Yorkshire mining town.

Margaret and David are very sweet together, most convincing as sister and brother, when she makes him promise to see Sheila. Here we are given a glimpse of David’s softer side.

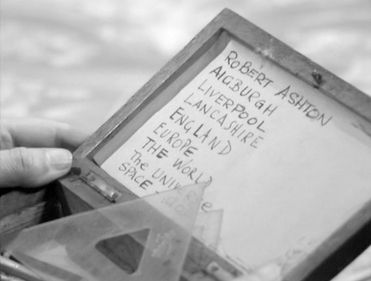

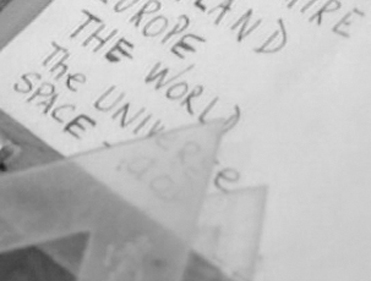

Not long after the Ashtons have learned of Robert’s death at sea, Jean is in the boys’ bedroom. As she turns over Robert’s mattress, it topples some books off the night stand. She leans down to pick them up and notices Robert’s old school supply box, on which is scribbled (in the boy’s own handwriting) “Robert Ashton / Aigburgh / Liverpool / Lancashire / England / Europe / The World / The Universe / Space.” There seems to be another word there as well (separated from “Space” by a dash or hyphen), but it is obscured from view by the plastic triangle. Can anyone tell me what that word might be? For your convenience, I have attached an image of the box and a close-up of the area in question.

Jean Farrington

My husband and I first watched most of this series when it was broadcast in 1970 and 71; to watch it now as adults who are about the age of Edward and Jean instead of being more like Margaret's age makes for interesting reflections. My judgement of Margaret was harsher the first time around.

That said, I found Richard Veit's comments about Margaret most interesting and agree with him that she draws one's attention throughout the series. While she is in many ways, the moral authority for her siblings and certainly takes on aspects of her mother's role in the family after Jean's death, I don't agree that she would necessarily have gone back to John and left Michael. I think with Michael she found not only someone with whom she shared passion, but an individual who understood who she was and emphathized with her as a person more than John could or did. She and John married so young and were both still relatively undefined as adults; the war interrupted what might have been a natural growing up together. After the war, the fact that John is attracted to the excitement and danger in and of Marjorie speaks to the lacks in the young Porters' marriage. The somewhat risque (risque only in the context of "A Family at War") scene in one of the post-war episodes when we see the two of them in bed and Margaret in a rather sexy negligee, however, does attest to the sexual side of their relationship. Even as these two seem to gradually get on to an even keel, I worry that their longterm marriage may become humdrum and cool like Edward and Jean's did.

John Finch

If we had continued the series into the post war world, Jean, you would probably have been right about John and Margaret. In developing the relationship in the wartime framework, however, we have to be aware of the different morality of the time. No so much the sexual morality as attitudes to the family and in particular, divorce.

So far as I can remember the wording on Robert's school box was as seen and ends with space. I copied it from a box of my own which, alas, I no longer have.

Richard Veit

I am curious what the rest of you think about the eight black-and-white episodes (Nos. 25-32) of “A Family at War.” Personally, I think these rank among the very strongest episodes, coming as they did during some of the most dramatic and pivotal plot developments in the entire series—John’s return, John burns his bridges, Margaret’s decision, Philip’s blindness, Celia’s discovery of Margaret’s infidelity, Jean’s death, etc. The eye quickly becomes accustomed to the lack of colour, and so (after the initial surprise and/or disappointment) these episodes work very well indeed. In a perverse sort of way, I am tempted to suggest that they may be even MORE powerful this way, somehow better setting the action in that WWII period of time. I will stop short of that, however, because I really do appreciate the effective use of colour in the other 44 episodes, and, after all, people living through the war years (despite the vintage movies we enjoy) actually did see things in colour! That said, I am glad that the series continued production throughout that difficult time of the trade union dispute, and I am certain that the original audience felt that way too, as continuity was maintained rather than having to endure a technical hiatus of several weeks. Come to think of it, I suppose that most viewers were not even aware of the change, as most television sets back then were black and white anyway.

Rhona Connor

I was unaware that "A Family at War" was in colour until I got the DVD's cos like you said we had a black and white telly. And you are right in some ways I enjoy the black and white ones more. You do not concentrate on the behind the scenes but the story itself and the characters are strong enough to pull it off. A lot of 70's dramas were a lot better than the ones today.

Wayne Wright Evans

This is perhaps one of the most well written of the series so far. Extremely well written and acted.

One certainly feels for poor Edwin - Jean is very uncomforting, but having just lost Robert and with the onslaught of illness, one has a certain empathy with her.

The black and white production made no difference whatsoever - in fact, I thought it was more atmospheric.

Mr Ashton senior's home reminded me of my grandparents' home in the Rhondda valleys in the 1960s. There too was the smell of the coal tips, and, yes, you could always rely on the pit boots waking you at 5.30 of a morning.

You can see in this episode that the Ashtons' marriage was doomed from the start. There must have been a certain amount of bonding within their relationship, as they have 5 children !!!

David continues to nauseate me. What a horrible character -- selfish so and so -- I am getting to dislike Michael as well.

Throughout the enjoyment of "A Family at War," I love the word Judies for girls. Is this a northern term, as I have not heard it before ??.

Richard Veit

I would like to add a few brief thoughts to Wayne's interesting comments about "Giving and Taking."

In my opinion, this particular episode presents one of Colin Douglas's finest, most gripping performances, when he pours his heart out to Jean. It is sad to see the lack of sympathy that Jean can display at such times of her husband's vulnerability, indicative of how far their marriage has deteriorated.

In hindsight, of course it is true to say that their marriage was doomed from the start, but I suspect that they had many compatible years before their marital troubles became acute. Jean's illness and Robert's death had much to do with the downward spiral, but so did the class differences between the two. Jean came from an affluent family, while Edwin was of coal-mining stock. Though usually quite subliminal in their marriage, the disparity of origins never did completely relax its hold on Edwin. We can see this class tension a bit more clearly in Edwin's strained relationship with Sefton Briggs (Jean's brother).

John Finch

I greatly appreciate both your comments on Episode 25. As you probably know, I storied the whole series myself, and I’m afraid I may have been guilty from time to time of pinching the best for my own episodes. As a matter of interest, I came across an outline the other day, my first outline for the series, covering the first 26 episodes. It is handwritten on four sheets of foolscap taped together, and this very tight format give date of episode, suggested writer, date script required, date edited script required, possible director, historical timescale, story theme, and main characters required in each episode, bearing in mind that actors had to be guaranteed so many out of thirteen. The budget for each episode was on the back of an envelope which I kept in my inside pocket. At budget meetings we of course had a real live accountant. And a real live producer eventually took the strain.

This now fading outline bears out what Sir Denis Forman said (then MD) that Family at War is the most cost effective series ever made. It is not even written in ink, but in pencil! And just little old me to write it.

I recently saw on television a shot of a conference for a current serial. There were some forty people sat round a very large table. I wont mention the name of the serial, but I would have been ashamed to be associated with what ultimately appears on the screen.